Lifelong Learner

/A varied life led Dr. Thomas Cutrer to his current work as the Texarkana Museums System’s volunteer archivist

By Ellen Orr

photo by shane darby.

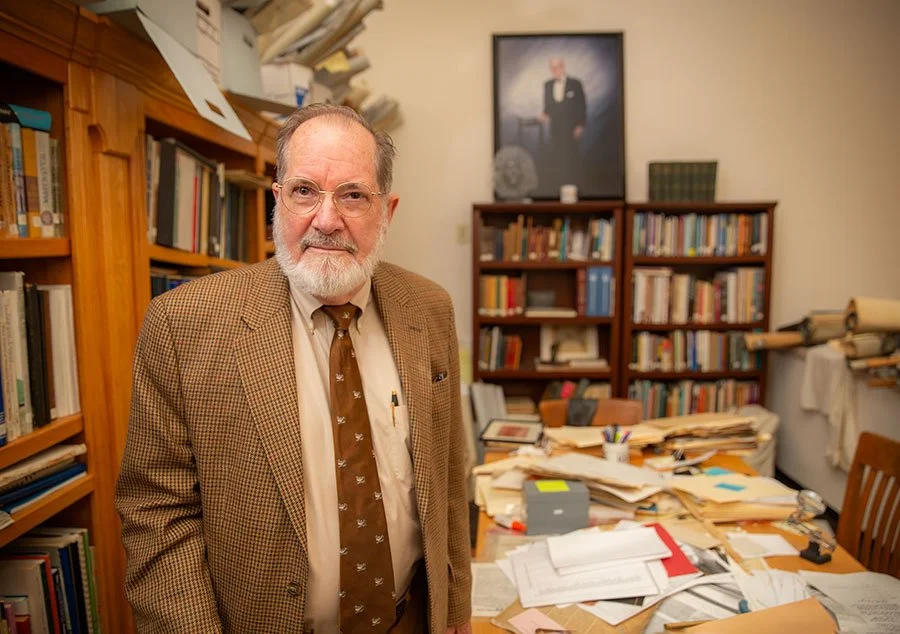

Dr. Thomas Cutrer says he’s on “Act 73” of his life. He is a Louisiana native, Vietnam veteran, historian, professor, published writer of over ten books, husband, father, hunter, volunteer, archivist, and—perhaps especially—a lifelong learner.

As a child, Tom was imbued with a love for the American South. His father died when he was only five years old, and he thus spent a lot of time on his grandmother’s remote farm in Tangipahoa Parish. “As we said: the Grand Ole Opry didn’t get there ‘til Monday morning,” Tom laughed. “It was pretty far back in the sticks. It was kid heaven. I had a dog, a .22 rifle, and my uncle’s boat, and I had free rein in the woods all day.”

Tom and his friends were enamored with the military, especially the Civil War. A dozen of Tom’s forebears had served in the Confederate Army, and, influenced by family lore and early reading, he became enamored of the idea of military glory.

Tom attended Louisiana State University, where he was an ROTC cadet colonel, and graduated with a history degree in 1969. He then was commissioned in the Air Force, acting as an intelligence officer in Vietnam. His time in Southeast Asia was life-changing and harrowing. From what he experienced, he determined that “we were not the good guys,” he recalled. “I went to the war as a hawk and came home as a dove.”

When Tom returned to the States, he set out to “get that taste [of war] out of my mouth,” he said. His passion for military history was justifiably soured, but he continued to be deeply interested in the South. Southern literature of the era was of the utmost importance to him.

“This was, of course, in the Civil Rights Era, and I was looking for things to make me proud of my region at a time when lynchings and burnings were a daily presence on the six-o’clock news,” Tom recalled. He devoured the writings of William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, Eudora Welty, and other writers of the so-called Southern Literary Renaissance, “the generation of southern writers who, like me, loved the place, and hated it, and wanted to tell the truth about it,” he said. “They were writing about me and my home. [Studying their works] was a way to appreciate the South, warts and all.”

To this end, Tom returned to LSU to pursue a master’s degree in English literature. At the time, Cleanth Brooks (the preeminent Southern literature critic and cofounder with Robert Penn Warren of The Southern Review) was retired from Yale and teaching for one semester only at LSU. As luck would have it, Tom nabbed a spot in Brooks’ class, and in him he gained a mentor. “He took me under his wing,” Tom said, “and I worshiped him.”

Following his master’s degree, Tom pursued a PhD in American studies at The University of Texas, for which he wrote the dissertation that would become his first published book: Parnassus on the Mississippi [LSU Press, 1984]. The book tells of the magical period when Baton Rouge was arguably the epicenter of American literary criticism. Writing this history would have been impossible without Brooks, who literally saved the Southern Review’s files from the dumpster where they were deposited upon the journal’s shuttering.

“I sit down here for hours at a time and don’t see anybody and just go through papers, and I find enjoyment in that.”

“At UT, so many of my classmates had degrees from Ivy League colleges, and I had my little degree from LSU—so I was a good deal intimidated,” Tom reflected. “But [having my dissertation published] gave me confidence that . . . I wasn’t just a dilettante. I could be a professional scholar.”

His success, he realized, would be earned not in spite of his background but in part because of it. “I have a foot in two worlds,” he said. “Mark Twain said that he was half border-ruffian from Missouri and a gentleman from Connecticut, and that is the best combination of things. I mean, the guys that I hunt and fish with are ‘good ole boys,’ and I love them dearly. And my faculty colleagues have been MacArthur Genius Award winners.”

While his many friends and colleagues contribute a great deal to Tom’s life, his greatest influence is a former classmate—”a gorgeous little Texas girl” who’d sat across from him at a seminar table at UT. “Emily was hard to pin down, but I was persistent, and we married in 1978,” Tom said. “Our daughter [Kate] was born in ’80, and our son [Will] in ’85.”

The young couple, freshly hooded, foresaw a straightforward life ahead: “I’m thinking, ‘Okay, we’re going to find a little college to teach our classes, write our books, and live happily ever after,” Tom recalled. They were both hired at Arizona State University, seemingly according to plan—except . . .

“Except Emily was a take-charge kind of girl,” Tom laughed. “I turned around, and she was my department chair. And the next thing I knew, she was my dean. Then Cal State–San Marcos made her provost, while I was still teaching at Arizona State, so I became a practicing bi-localist, driving back between Phoenix and San Diego every week.”

Then, in 2013, Emily was offered the presidency at Texas A&M University–Texarkana. “She asked, ‘Would you go to Texarkana with me?’” Tom relayed. “I said, ‘Would you buy me a new truck?’ She did, and we lived happily ever after.” Tom was hired as an adjunct in the history department.

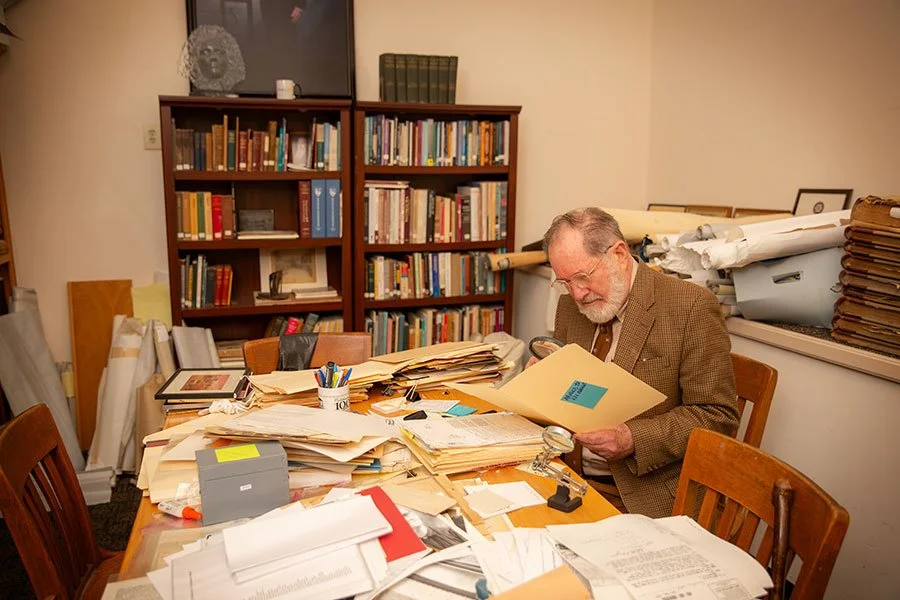

In the winter of 2022, after a successful ten-year tenure in her role as president, Emily announced that she would be retiring mid-2023. Around that time, Tom retired as well and began filling his newly vacant Thursdays volunteering at the Museum of Regional History, indexing 19th-century Texarkana newspapers. Then, in late 2023, he transitioned into his current role, as volunteer archivist for the Texarkana Museums System. He works at the museum four days per week, sorting through innumerable documents bestowed to the museum. When he began, boxes were stacked wall-to-wall and floor-to-ceiling in many rooms. “Sadly, there was more stuff than the staff could take care of, so there were literally hundreds of boxes, and opening every one of them was like Christmas,” he explained. “A lot of it, frankly, was trash—but a lot of it has been just wonderful.

photo by shane darby.

Tom describes himself as a person content with solitude. “I’m something of a hermit,” he said. “I was an only child, and I spent a lot of time as a child alone, so I’m not uncomfortable with that. I sit down here for hours at a time and don’t see anybody and just go through papers, and I find enjoyment in that.”

Though he may not speak to another person for hours at a time, Tom still spends his days in intimate (if one-sided) relationship with others, though these others are Texarkanans who have been deceased for many years. Through rediscovered letters, diaries, and various other documents, Tom has gotten to know countless individuals. For instance, he has gotten to know Rachel Moores, one of the founding residents of Texarkana, through her letters and journals discovered in someone’s attic. He transcribed, edited, and compiled these into a book, which is currently in press.

Though he may be content convening only with those long past, that is not to say that he doesn’t delight in his daily interactions with the living. “[TMS Executive Director] Emily Tarr is a delightful woman and a good friend; everyone on the staff here is fun, the people who come in to do research are fun, and I do get a chance to meet people and talk about Texarkana history—and that’s fun, too,” he said. “But I’m learning, and that’s primarily what I’m about.”