Ask Dr. Ben

/

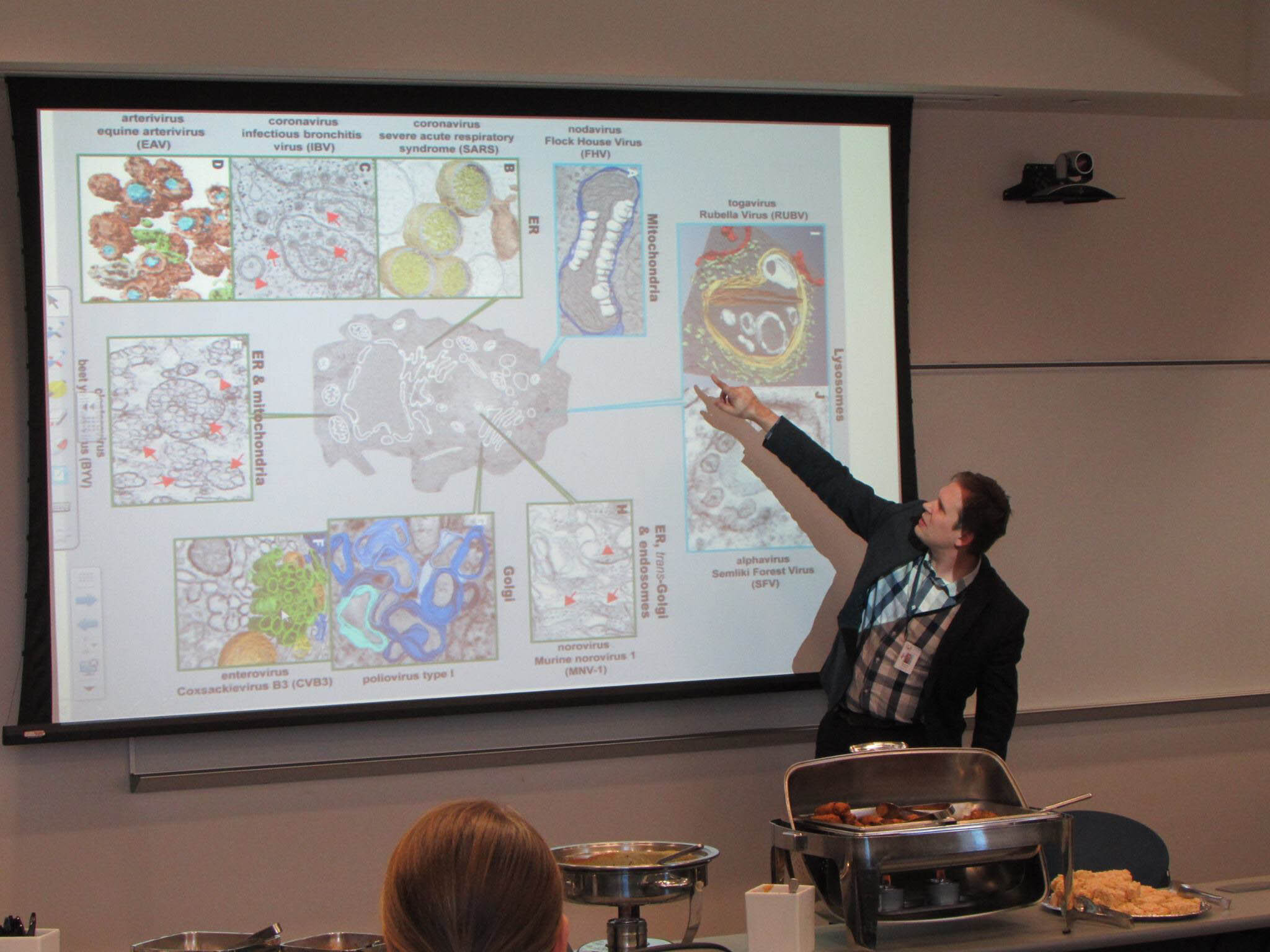

Dr. Ben Neuman, world-renowned virologist and head of the Biology Department of Texas A&M University-Texarkana, discusses life, science, and COVID-19

by: VICKI MELDE

photo by JOHN BUNCH

Dr. Neuman presents an Honors Colloquium at Texas A&M University-Texarkana in 2018.

Please tell us about growing up – your family, where you were raised, your fondest memories. What kind of child/teenager would you say you were?

I was born in northeast Ohio – my mother had moved around some during her childhood but my Dad was from a small town there, and before he went to law school at Vanderbilt I spent my first years living in a cottage near Lake Erie. I am the oldest of four children, and there was enough of a gap between me and my brother, Jake, that I ended up mostly keeping to myself.

I was very short-sighted – that might be a good place to start. I spent a lot of time holding things like stamps up close to my face to see the details. I saved up and bought a little microscope where the eyepiece screwed into the top of the tube, and you had to lean over and look straight down the barrel to see anything. My grandmother introduced me to fossils, and they just seemed like treasure that you could pick up and bring home if you could pick out the details that pointed to something that had been alive once. I walked up and down the beach of Lake Erie in the summer with my shirt pulled up to make a basket that was full of rocks, mostly around the size of a good steak but sometimes much bigger. We ended up with a lot of those in the house.

My grandparents had a farm about an hour north of where we lived. I liked picking blackberries, and wandering the woods trying to follow a thin yellow stripe of sand that must have been the edge of a beach at one time. I was a little nervous about being in the field at the same time as the cows – I think there weren’t more than three at a time, mostly for milk.

Nicola and I got married at that farm in 2000 – and it is still in my extended family’s possession.

In 2019, Isaac, Theia, Ben and Nicole visited Davidson Glacier in Alaska.

I was a good student, I skipped a grade and graduated as valedictorian of my class but always looked at it as a thing to get through so I could think about other, more interesting stuff. I had a fascination with Egyptian hieroglyphs – the idea of a secret code between me and the dead was appealing

Were you “into science” growing up? How did you know you wanted to enter academia – and Biology/Virology, in particular?

I was probably more into collecting than science at first. In the two homes I grew up in, I had a room that was previously the upstairs kitchen back when two families lived there, so there were lots of cupboards for storing things, and I certainly filled them up. A lot of that was collections of seashells from visiting relatives in Florida – the beach was another one of those treasure-fields where you never quite knew what you would find.

Once I had these collections, the next natural thing was to want to show them off, so I thought I would like to be a museum curator. My first museum had some of what I was convinced were either Viking or shipwreck relics from Lake Erie – mostly bits of driftwood and things from the houses that erosion was always pulling into the lake.

From there, I went to thinking running a greenhouse might be fun – propagating exotic little plants for a living. One summer I had the great idea to disassemble a Christmas cactus into its segments – I had heard they could regenerate. And when they didn’t start regenerating after a day or two, I borrowed one of my father’s insulin syringes and injected each of the little cactus-nubs with concentrated Miracle-Gro® to give them a little boost. It didn’t go well – they developed these soft, wet sores and then just deflated and died. Experiments don’t always work out.

Please tell us about your education – did you start out knowing you’d earn your Ph.D.?

I hadn’t given any real thought to viruses until my senior year at University of Toledo – I had got a full ride there on a National Merit scholarship, which meant free tuition and a place to stay plus $600 a term that I could spend at the campus shop. When it got near the end of term, and I had some money left, I ended up bringing home crates of Snapple.

I had the good fortune to end up doing my senior project in a virus lab with a person called Scott Leisner. He worked on Cauliflower mosaic virus, which caused little yellow spots and streaks on the leaves of a variety of plants. My job, and the reason it appealed to me at the time, was that I could plant turnip seeds, and grow them in the greenhouse until it was time to infect. We ended up treating the turnips with an anti-HIV drug, and it worked reasonably well, which was kind of neat.

In my junior year, I had gone abroad for a year to take classes in England – that was a giant challenge, and the first time I really had to work at school. The students there had been focusing and were far ahead of me, in terms of understanding. Over there, you would specialize – first to around eight or nine subjects, and then around age 16 down to around three subjects, and that is all you would study. From the moment British students arrived at university in the biology program, they would be taking 100% biology classes – it was certainly different than what I had experienced at Toledo. It ended up working out well, and I met a very nice English girl called Nicola over there, but more about her in a bit.

I had been told all the way since elementary school that I was probably going to make a good doctor, and up to that point, it seemed like something I could probably do, and a reasonable way to make a living. After arriving back from the year in England, I finished up my degree except for two required Latin classes that were spaced out in such a way that you couldn’t take them in the same year. So I became a fifth-year senior.

To get ready for medical school, I volunteered at the medical school in town, which was independent at the time but is now part of the University of Toledo. I found the position through a contact from my undergraduate project mentor, Dr. Leisner, and it turned out to be working on a different virus of mice – the mouse coronavirus. At the time, I was mostly looking for something to do while waiting for medical school, but I really liked the problem solving and planning in experimental science. After a year of work in the lab, I had a decision to make – I had a full scholarship to the MD-PhD program at the Toledo medical school, or my mentor there, Dr. Sawicki knew a person over in England who also worked on coronavirus, and was looking for PhD students. I was never all that keen on people or blood, and I really liked virus work, so it ended up being an easier choice than you might imagine. I went for the PhD, minus the MD.

It was at a little government-funded research institute in England that was very focused on diseases of farm animals, called the Institute for Animal Health. I struggled at first to catch up to where the other PhD students were, but after a difficult year where it seemed like everything I tried just failed, things started to click. The place where I worked wasn’t a university, so they registered me with Reading University which was both reasonably priced, and just down the road, so to speak. I’d visit Reading twice a year to give an update talk, and that’s where I got my PhD. Later, I ended up working at Reading University, after a stint at a big research institute in California.

Please tell us how you and Nicola met and what you admire most about her.

I met Nicola on my first trip to England, in my third year of university when we were both 19. I was part of a group of seven American students that had dwindled down to three by Christmas of that first year (the others were too homesick and went home!). Apparently Nicola first saw me when we were marched fresh from the airport into a big seminar room.

A few days later, after arriving at the coast, we were both scheduled to be in the second wave of minibuses to go from our accommodation, in an old Victorian artillery fort, down to work in some mud flats. We ended up talking then, and then talking more up on the outer wall of the fort, looking out over the ocean. We talked for hours and really hit it off – that’s how it all started. What I liked about her then is the same as now – she liked biology, didn’t mind getting muddy, and was always going out of her way to try to help people. It’s hard to put it in words – I just really liked her and the way she thought about things, I had never met anyone like her before. For the next two years, with me back in the U.S. and her finishing off her undergraduate degree in England we embarked on a long distance relationship. All of this was, of course, way before cell phones or FaceTime, or even before email became the common way to communicate.

We called (internationally from payphones!) and wrote to each other, with a couple of visits until my PhD started in England, and I could finally walk across some fields to the next big town and then catch a train, the tube and another train to visit her over on the other side of London each weekend. That was actually a big attraction of the PhD – it meant I got to be closer to her.

During 2012, Dr. Neuman (far right) went on an Arctic Microbiology field course with students and professors from University of Reading (UK) and University of Akureyri (Iceland). Here, they are pictured at a lava tube cave near Akureyri, Iceland.

From the age of 16, Nicola has always spent time volunteering in whatever community she finds herself – we have moved a fair amount in our married life, and in each place she looks for some way to give back. Most recently, she has volunteered to be part of the newly formed Evergreen Life Service Development Committee in Texarkana – I like that she sets that example for our children – even though she has a job and a family she always makes time for other people who are less fortunate. Her mantra is “bloom where you are planted” – and she certainly lives by it.

And your children, please tell us their names, ages, and something interesting about each of them. And please include family pets …

Isaac is our oldest, 16, and is about to be a junior at PG High School. He plays trombone in the band and is really good at it – much better than I ever was – and is going to be the assistant drum major this year, which is pretty neat. He is also a member of the Texarkana Youth Symphony Orchestra as of this year but hasn’t been able to perform with them yet due to the lockdown. He recently took part in the HOBY leadership conference online.

Theia is our youngest, 13, and is going into the eighth grade at PG Middle School. Her big extracurricular thing is being in the StarSteppers drill team, and she works really hard at it, doing chassés and exercise kicks around the house. She also plays the trombone in the middle school band – we joke that trombone playing is a family obligation whether she likes it or not (I played, my grandfather played, and I have uncles and cousins who play, too). She takes very good care of our animals, all of which she has convinced us to “rescue” – we have five cats. And, of course, Theia somehow convinced me to get our corgi, during quarantine – it only took her 13 years! Apparently she is running with that success and now lobbying for a horse.

How do you balance your extremely busy schedule – especially now in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic – with being a husband and father?

At the moment, it’s hard. I am working for the summer on COVID stuff down in College Station, but drive back to see everyone on weekends. I suppose it helps a bit that we are all sort of house-bound because of the virus at the moment – I can see Nicola and the kids almost non-stop during the weekend. None of this would work at all if it wasn’t for Nicola, of course, keeping things running in Texarkana. Like most people involved in coronavirus research, I am not taking any breaks during a pandemic – time is of the essence. It’s intense but necessary.

You have been sought for interviews and insights by news organizations all over the globe – tell us about that experience.

That was a bit scary at first, but I kind of get a kick out of it now. My role has always been to help explain the science of how viruses work in a way that is a little easier to understand. It’s something like being an expert witness in court, I imagine. My job is to try to stay neutral and help explain the facts as we understand them.

There have been some wild ones – when I was in the UK I ended up (with no idea beforehand) debating a Member of Parliament over Ebola regulations. I got to be on a show called “Africa Today” with a host from the Xhosa people who had a click-consonant in her name and was funded by Iran to talk about HIV. I’ve been on the couch on “Good Morning Britain” a few times, getting to chat with the makeup artists and the other guests in the green room, which was a lot of fun. Recently, I was featured in the Russian newspaper, Pravda, in the same week as I was on Voice of America in Russia – both talking about the spread of COVID-19. I am pretty sure those two are usually on the opposite sides of an issue, but whoever wants to talk about viruses, I try to help.

When the MERS coronavirus spread to South Korea, some of my comments even got picked up on Kim Jong Un’s personal website, which is really something else, if you ever get a chance to browse it. I’ve got a little spreadsheet where I keep track of media appearances, and I’m up to around 130 countries where one of my interviews or quotes has appeared in a local newspaper or station. I just like answering questions, and when the interview starts, it’s easy enough to forget about the camera and just focus on listening and trying to do a good job. Sometimes it just really clicks, but if you were to ask me after the interview what I just said, I can never remember the exact wording.

And please tell us about the work you’ve been doing on COVID-19. You were a member of the committee that named this virus – correct?

I had wanted to join the committee that decides on the names of coronaviruses for quite a while, and finally got my chance when I helped discover some new corona-like viruses in a frog and a sea slug, respectively. I guess it’s like a magician’s guild in that way – there are probably other ways to get in, but usually it happens because you show the other members something new.

At the coronavirus meetings, we pass around spreadsheets with suggestions for new virus names and debate the best way to name things – I really like that aspect of virology, too. When it came to the new virus, the head of the naming committee ran some analysis that confirmed that this virus was such a close relative of the original SARS coronavirus that it had to be incorporated into the same species. I’m not the one who slapped the number two on the end of SARS-CoV-2, but I was one of the ones who agreed that was a reasonable thing to do. At the time we named the virus, the disease didn’t have a name yet, and I was hoping the WHO might settle on Type 2 SARS, by analogy to the virus name and Type I and II diabetes, but they decided to go in a different direction and COVID-19 makes a lot of sense, too.

What is the best advice you can give the magazine’s readers about avoiding COVID-19? Do you believe there will be a vaccine anytime soon – and are you involved in this research?

Wear a mask and avoid contact with other people, to the extent that you can. You can let your guard down at home, but when you are out in the world, it’s showtime and your actions matter more than you think.

I am helping a group of very smart quantum physicists for the summer at the Institute for Quantum Science and Engineering at TAMU. It is an amazing experience, unlike anything I have ever done before. They are trying to make better, more sensitive, more useful tests for COVID-19, and it is a real privilege to be able to help. I am also working with groups here and in Iraq on developing COVID vaccines, which is a completely new area of science for me.

The “Ask Dr. Ben” artwork for Facebook and YouTube was created by his friend, Pete Starling of Electrographica.

Please tell us about “Ask Dr. Ben” – your science group on Facebook has quite a following. How did the idea get started and how do you manage to keep up with it with everything else you have going on?

“Ask Dr. Ben” was entirely Nicola’s idea, and it was a good one. We were getting emails and texts from friends and family at the beginning of the outbreak asking questions about the virus, and it seemed like it might be helpful to put the answers out there where other people could see, in case they had the same questions. She was especially aware that some children were feeling rather anxious about this scary new virus, and in the beginning we answered a lot of questions from kids to try and help them figure it all out. Kids tend to ask the most wonderful questions – How big is the virus? What color is the virus? Will the tooth fairy still come during the pandemic? Will this virus change me from a girl to a boy? Kids take their cues from their parents so we wanted to try and give them both the tools to stay informed, at a level appropriate for all ages.

Every morning before work, Nicola sends me a list of some questions, or I pick a few new papers about the virus to review, and then I record a couple of short answers before work. She does the rest – the editing, the posting, managing the group, engaging with all the members. It’s one more of the many ways that Nicola keeps things running, and I am lucky she has a real flair for it. I never would have imagined I’d have my own Dr. Ben theme song, but a friend from the UK, Mike Hewitt-Brown, sent us one, and I have to say, it’s pretty catchy. “If you have a question that needs an answer, and the question is about virology ... Dr. Ben (Dr. Ben).” Sometimes we get questions about fossils or mask fashion. I just hope all of this helps somebody and makes a complicated, worrying thing feel less so. We have had some really lovely, kind messages of support, and that’s what keeps us going.

photo by JOHN BUNCH